War and peace represent two vastly different paths for societies, each with profound economic, social, and structural consequences. Waging war incurs enormous direct costs – from military expenditures to physical destruction – and indirect costs that echo for generations in lost lives and stalled development. By contrast, international cooperation and peace-building require far fewer resources yet promise long-term shared gains in prosperity and human well-being. This analysis compares the cost of war versus the cost of cooperation, examining economic impacts, social and structural effects, and weighing the touted short-term economic benefits of war against its devastating long-term consequences. Historical evidence, economic data, and theoretical models all suggest that the dividends of cooperation far outweigh the fleeting gains of conflict, and we explore how a cooperative global economic system could function to sustainably meet the needs of all people.

The Economic Costs of War vs. Peace

Massive Financial Costs: War is a costly undertaking. Global conflict and violence cost the world on the order of $14 trillion per year (about 10% of global GDP) in recent years weforum.org weforum.org. This translates to roughly $5 a day for every person on the planet weforum.org– resources that could otherwise be invested in productive and humane ends. For countries directly embroiled in conflict, the economic toll is devastating: in 2016 the costs of violence were estimated at 67% of GDP for Syria, 58% for Iraq, and 52% for Afghanistan visionofhumanity.org. War often obliterates physical capital and productive capacity, causing economic output to plunge. A study of 150 wars since 1870 finds that on average a war reduces the affected country’s GDP by about 30% over five years, as factories, buildings and infrastructure are destroyed ifw-kiel.de. Even neighboring countries suffer economic fallout – losing around 10% of output on average due to war-induced trade disruptions, refugee flows, and regional instability ifw-kiel.de. In the case of the ongoing Ukraine conflict, projections based on past wars suggest Ukraine may lose about $120 billion in GDP and nearly $1 trillion in capital stock by 2026 as a result of the invasion ifw-kiel.de. These staggering losses underscore how war ravages economies at both national and regional levels.

Long-Term Drag on Growth: The negative economic impacts of war are not just immediate but persist for years or decades. War-inflicted countries often experience slower GDP growth long after the fighting stops. For example, nine years after its civil war ended, Sierra Leone’s GDP was still 31% lower than it would have been without the war’s legacy visionofhumanity.org. Globally, research suggests that if all violent conflict since 1970 had been avoided, world GDP would be about 12% higher today than it actually is warpreventioninitiative.org warpreventioninitiative.org. War diminishes growth by destroying human capital (through deaths and disruption of education), deterring investment, and diverting public finances from productive uses to military needs war prevention initiative.org. In contrast, peaceful and stable countries consistently outperform conflict-torn states in economic growth. Over the past half century, per capita GDP growth has been three times higher in highly peaceful countries compared to countries with low levels of peace economicsandpeace.org. Peace creates an environment conducive to investment, innovation, and commerce, whereas war breeds uncertainty and capital flight. In short, economies flourish with cooperation and stability, and they stagnate or regress with conflict.

Debt and Opportunity Costs: Another economic strike against war is how it is financed. Major wars are often paid for with heavy government borrowing and higher taxes, which can simulate a short-term stimulus but impose steep costs later visionofhumanity.org. During World War II and other large conflicts, GDP rose in countries like the United States due to massive war production, giving rise to the notion that “war is good for the economy”visionofhumanity.org. However, this is largely an illusion. Wartime GDP gains often reflect armaments and rebuilding that merely replace what’s been destroyed, rather than net new wealth – a classic “broken window” fallacy where destruction masquerades as growth. In fact, wartime financing crowds out civilian investment and consumption, and the post-war period is frequently burdened by debt repayment and inflation visionofhumanity.org ifw-kiel.de. For example, the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were funded heavily by debt; estimates including future veterans’ care and interest payments put the total cost of the 20-year “War on Terror” at around $8 trillion for the U.S. alonebrown.edu brown.edu. These debts will be paid by future generations, siphoning funds away from domestic priorities. The opportunity cost of war is enormous: money spent on tanks and bombs is money not spent on schools, hospitals, or infrastructure. Indeed, the annual global cost of armed conflict (circa $14 trillion) exceeds the world’s total yearly spending on health care ($7.2 trillion in 2015) and rivals what is spent on education fcnl.org. It dwarfs the resources needed to address humanitarian goals – for instance, the $267 billion per year that could end global hunger is just a tiny fraction (around 2%) of what the world loses to violence fcnl.org. In economic terms, choosing war is an astoundingly inefficient allocation of resources compared to choosing cooperation and peace.

Social and Structural Impacts of War

Humanitarian Catastrophe: Beyond spreadsheets and GDP figures, the true cost of war is measured in human lives and social devastation. War inflicts suffering on a massive scale. In the 20th century, major wars killed on the order of 100 million people, and modern conflicts continue to take a heavy toll. Today, about 1.4 million people die violently each year due to wars and other conflicts weforum.org, and for every battlefield death it is estimated 40 more people are injured weforum.org, often maimed for life. The societal trauma of large-scale violence is incalculable – families are torn apart, communities uprooted, and whole generations grow up in fear and grief. War zones experience spikes in atrocities, gender-based violence, and the collapse of basic services. As conflicts drag on, they create millions of refugees and internally displaced persons; more than three-quarters of the world’s refugees are hosted in low-income, fragile states that can ill afford the strain weforum.org. The social fabric frays under such pressure. For example, wars in the Middle East and North Africa over the past decade have left tens of millions in need of humanitarian aid – 13.5 million people in Syria, 21 million in Yemen, 8 million in Iraq, and so on worldbank.org – overwhelming both local and international aid capacities. The poverty rate soars in war-torn societies, as seen in Yemen where over 80% of the population is now impoverished amid conflict worldbank.org. Education and healthcare systems collapse or barely function; children in conflict zones lose years of schooling and are often traumatized, undermining the development of human capital. These social costs – death, displacement, trauma, lost education – represent lasting wounds that hinder a country’s ability to recover even decades after the guns fall silent.

Infrastructure and Institutional Destruction: War literally shatters the physical and institutional structures that hold societies together. Bombs and artillery turn cities into rubble, destroying homes, factories, power grids, roads, and hospitals. For instance, in Syria and Iraq, persistent conflict has left their per capita incomes roughly 25% lower than they would have been without war, reflecting the destruction of infrastructure and industryworldbank.org. Rebuilding war-ravaged infrastructure can take tens of billions of dollars and many years – resources that could have been invested in new development rather than just replacing what was lost. The structural damage is not only physical: wars often collapse governing institutions and the rule of law. Administrative systems break down under conflict, leading to lawlessness, corruption, and the erosion of trust in authority. Civil wars are especially corrosive to institutions; they can turn functioning states into failed states. Public health crises and famine frequently accompany wars, as agricultural systems are disrupted and disease outbreaks spread unchecked (historically, more soldiers have died from disease and malnutrition in some wars than from combat). Moreover, war’s impacts are intergenerational – malnutrition in wartime can stunt children’s growth, landmines left behind can kill or maim civilians for decades, and the environmental damage (oil well fires, defoliated forests, polluted battlefields) can render areas unlivable. In sum, war not only destroys what exists – it also destroys the potential for future progress by crippling the infrastructure and institutions needed for a healthy, productive society.

Violence Breeds Further Instability: The social and structural upheavals caused by war can create vicious cycles of conflict. Societies emerging from war often confront devastated economies, rampant unemployment (especially among youth), and grievances over past atrocities – conditions ripe for extremism, crime, or relapse into conflict if not carefully managed. Studies of fragile states find that a civil war greatly increases the risk of future conflicts, trapping countries in a conflict cycle that is extremely hard to break. For example, the persistence of violence and poor governance in parts of the Middle East and Africa has fueled a rise in violent extremist groups, despite massive military efforts to defeat them fcnl.org fcnl.org. In contrast, peaceful cooperation provides the stability in which social capital can grow and disputes can be resolved without bloodshed. Countries that invest in inclusive institutions, equitable development, and justice – the building blocks of a cooperative order – are far less likely to fall into war. Thus, the structural damage war causes to economies and governance isn’t easily repaired; it often leaves a legacy of instability that undermines development and security long after the war itself ends. This underscores that preventing war and fostering cooperation is not just morally preferable, but crucial to breaking cycles of underdevelopment and violence.

War’s “Benefits” – Myth or Reality?

Proponents of military build-up sometimes argue that war or high defense spending can benefit an economy by creating jobs, spurring technological innovation, or boosting certain industries. History offers some limited evidence of short-term economic boosts from war, but these must be weighed against the overwhelming long-term costs already discussed. It is true, for instance, that World War II ended the Great Depression in the United States, as massive war production mobilized idle factories and workers. GDP growth surged during WWII, as well as during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, fueling the argument that war can be an economic stimulant visionofhumanity.org. Large conflicts also often coincide with rapid innovation in technology – the world wars and the Cold War gave birth to radar, jet engines, nuclear energy, computers, and the internet, among other breakthroughs. Military R&D has produced useful civilian spin-offs like GPS navigation and microwave ovensvisionofhumanity.org

. Additionally, the military-industrial sector – private contractors supplying arms and equipment – profits greatly during wartime, and arms-exporting countries see revenue windfalls. Major powers not suffering combat on their own soil (for example, the U.S. in World Wars I and II) can emerge economically strengthened relative to devastated rivals, at least in the immediate aftermath of war. These factors show that some economic interests can benefit from war – chiefly arms manufacturers, military personnel employment, and industries tied to defense.

However, extensive research indicates that these short-term or narrow benefits do not outweigh the broader destruction and economic distortion caused by war. In fact, many economists label the idea that “war is good for the economy” a dangerous myth visionofhumanity.org. The apparent boosts in output during war are often an artifact of how we measure GDP – all spending counts as positive, even if it’s producing weapons or rebuilding what was destroyed visionofhumanity.org. As one peace economist noted, “It counts that which is destructive for society in the same way as what is good” visionofhumanity.org. Resources poured into making bombs could have built schools or businesses; their explosion yields no lasting economic gain. When we consider opportunity cost, war is a terrible deal. Numerous researchers have pointed out that investing the same money in civilian industries or research yields greater long-term growth than military spending visionofhumanity.org. For example, money spent on military R&D often produces accidental civilian benefits as a by-product, whereas the same money in direct civilian R&D is specifically targeted at improving economic productivity visionofhumanity.org.

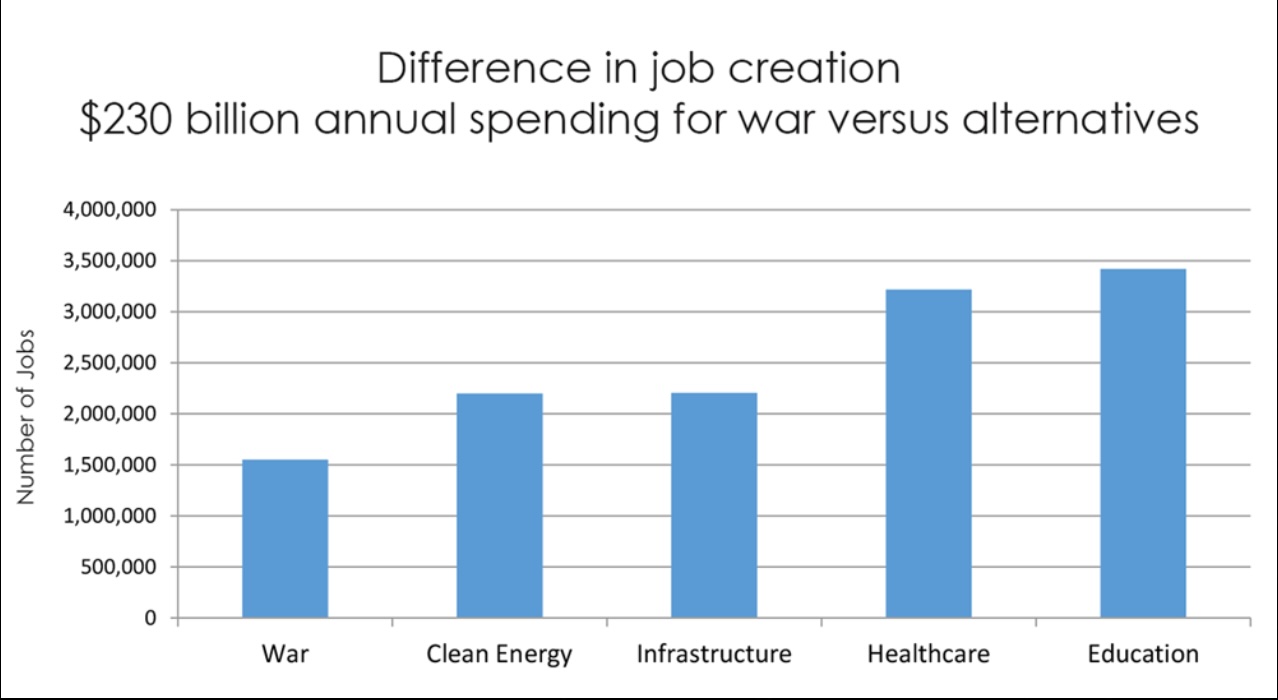

Moreover, military spending is an inefficient job creator compared to other forms of spending. Dollar for dollar, federal spending on education, healthcare, clean energy, or infrastructure creates far more jobs than defense spending brown.edu. One study found that $1 million spent on the military creates about 7 jobs, whereas the same $1 million would create 19 jobs in education or 14 jobs in the healthcare sector brown.edu. War industry jobs may be high-tech, but they are relatively few; investing in peacetime industries employs more people and yields goods that raise living standards, not just armaments. War can also distort a nation’s economic structure – during conflicts, skilled labor and materials are diverted to military purposes, often leading to shortages and rationing of consumer goods. In extreme cases, such as total war mobilization, civilian consumption is suppressed (e.g. Americans in WWII could not buy new cars or appliances for years because factories were making tanks and bombers). Higher taxes and inflation frequently accompany wars ifw-kiel.de, eroding household incomes. And while some companies thrive (weapons manufacturers, private military contractors), other sectors suffer from instability and uncertainty. It’s telling that peaceful countries, not war-torn ones, consistently achieve higher economic performance – whatever spur war might provide is more than canceled out by its destruction. As evidence, during 1960–2016 the most peaceful nations enjoyed triple the per-capita GDP growth of the least peaceful ones economicsandpeace.org. In short, the so-called “economic benefits” of war accrue to a limited few and are often short-lived, whereas the costs – lost output, debt, destruction, human capital loss – are systemic and long-lasting. War is fundamentally a zero-sum or negative-sum game, whereas cooperation allows for positive-sum outcomes where all sides can gain.

Job creation per $1 million spent: Military spending yields far fewer jobs than the same spending on education, healthcare, clean energy, or infrastructure. In this comparison of a $230 billion expenditure, war-related outlays (leftmost bar) support far fewer jobs (≈1.5 million) than equivalent spending on clean energy (≈2.2 million), infrastructure (≈1.9 million), healthcare (≈3.0 million), or education (≈3.7 million). This illustrates the greater employment bang-for-buck when investing in cooperative social goods rather than the military brown.edu.

The Cost of Cooperation (and the Peace Dividend)

If war is so costly, what about the alternative – cooperation and peace? Peaceful, cooperative approaches also require investment and effort (for example, diplomacy, foreign aid, peacekeeping missions, and international institutions all have a financial cost), but these costs are minute compared to the price of war. Consider the United Nations: the entire UN peacekeeping budget for a year is on the order of $6 billion, which is roughly 0.3% of annual global military spendingbetterworldcampaign.org. In other words, the world spends hundreds of times more on war and armaments than on peacekeeping and conflict prevention. The “cost of cooperation” – funding dialogue, mediation, economic development assistance, etc. – is a bargain in comparison. For example, development aid aimed at preventing state failure or famine might cost a few billion, whereas a war triggered by state collapse can cost trillions. Investments in preventive diplomacy and peacebuilding yield enormous returns. Research by the Institute for Economics and Peace indicates that each dollar invested in peacebuilding can save about $16 by reducing the cost of conflict down the road. This highlights a huge peace dividend: money spent on cooperation and stability pays off many times over by averting the far greater damages of war.

From an economic perspective, a cooperative global system unlocks positive-sum gains. When nations trade freely and collaborate, they can specialize in what they do best, leading to greater overall output (the classic gains from trade in economics). International cooperation also allows the sharing of knowledge and technology, boosting innovation worldwide. One historical example is the European Union – by cooperating and integrating their economies after World War II, European countries eliminated the costly military rivalries among themselves and created a single market that has greatly increased prosperity. The “peace dividend” in Europe after 1945 included decades of economic growth; resources once spent on armies were redirected to industry, welfare, and infrastructure. The cooperative effort of the Marshall Plan – a U.S.-funded European Recovery Program – cost about $13.3 billion (around $140 billion in today’s dollars) afsa.org, a fraction of what the war had cost, and helped war-torn nations rebuild their economies afsa.org afsa.org. This investment in cooperation paid off by revitalizing trade partners and stabilizing a region that might otherwise have descended into chaos. In contrast, the punitive approach after World War I (imposing crushing reparations on Germany without adequate cooperation or aid) is widely seen as contributing to economic collapse and the rise of another war. History thus shows that the cost of helping former adversaries and investing in shared prosperity is far less than the cost of letting conflicts fester or resume.

International cooperation can also spread costs in a fairer way. Solving global problems – whether preventing wars, fighting pandemics, or addressing climate change – benefits everyone, but requires collective action. A cooperative global economic system would see nations pool resources to tackle common challenges, which is far cheaper per country than each nation acting alone or, worse, falling into conflict over resources. For instance, rather than nations fighting wars over oil or water, cooperative investment in sustainable energy and water-sharing agreements would meet needs without bloodshed. The cost of such cooperation is relatively small. The United Nations estimates that achieving universal access to primary and secondary education worldwide (one of the Sustainable Development Goals) would require an investment of roughly only 3% of global military spending unfoldzero.org. Likewise, to eliminate extreme poverty and hunger – raising the living standards of the poorest – would cost on the order of 10–15% of global military expenditureunfoldzero.org. In other words, a modest reallocation of what the world already spends on arms could literally end hunger and illiteracy. A cooperative global system would prioritize such life-improving investments. The benefits of doing so would be immense: higher education levels and poverty reduction are strongly linked to lower conflict risk, creating a virtuous cycle of peace and prosperity. By contrast, the current militarized approach yields a vicious cycle, where high military spending drains resources from social needs, which can in turn breed the very instability used to justify more military spending.

Envisioning a Sustainable Cooperative Global System

What might a truly cooperative global economic system look like, and how would it meet human needs sustainably? In essence, it would be a world order where nations see peace and shared prosperity as common interests, and structure their economies and institutions accordingly. Several key features can be envisioned:

-

International Institutions and Rule of Law: A cooperative system relies on robust international institutions to mediate disputes and enforce agreements, so that nations trust that their rivals will not simply cheat or resort to force. Strengthening bodies like the United Nations, international courts, and regional unions is vital. Instead of conflicts being settled by war (with “winner takes all” outcomes), they would be settled at the negotiating table via treaties, arbitration, and law weforum.org. This requires commitment to international law and perhaps reforming institutions (for example, a reformed UN Security Council more reflective of today’s power distribution weforum.org). The cost of funding these institutions and diplomatic efforts is tiny next to war budgets. And when disputes are resolved peacefully, trade and cooperation can continue with minimal disruption.

-

Preventive Diplomacy and Conflict Prevention: A sustainable peace-based system would invest heavily in preventing wars before they start. This means addressing root causes of conflict – poverty, inequality, injustice, and insecurity – through cooperative efforts. Programs that support inclusive governance, economic development in fragile states, and early mediation in emerging crises can stop conflicts from igniting weforum.org. It is far cheaper to pay facilitators and development projects now than to pay for peacekeepers and reconstruction after a war. For example, supporting food security and climate resilience in vulnerable regions can prevent resource scarcity conflicts. Theoretical models in peace research (such as game theory) show that building trust and communication (akin to iterated “prisoner’s dilemma” cooperation) reduces the incentive for betrayal or aggression. In practice, this might involve confidence-building measures, arms control agreements, and cultural exchanges that humanize former adversaries. The world has seen successes in this realm – for instance, decades of arms control treaties (like the Non-Proliferation Treaty, strategic arms limitation agreements, etc.) curbed the arms race and reduced the probability of great-power war, saving untold resources that would have been spent on an even larger nuclear arsenal. Every dollar or effort spent on preventing conflict yields a huge payoff by avoiding the far higher cost of fighting one – recall the finding that $1 in peacebuilding can save $16 in conflict costs.

-

Economic Interdependence and Fair Trade: A cooperative global economy would emphasize interdependence – countries trading and investing in each other’s success. The more economically linked nations are, the more costly war between them becomes, creating a deterrent. This idea traces back to classical liberal theory (Immanuel Kant’s vision of “perpetual peace” highlighted trade as one pillar) and has modern evidence: for example, the European Union’s intertwining of economies is credited with making war between France and Germany unthinkable after centuries of conflict. To function for all, global trade must be fair and inclusive, so that all participants see gains. This might involve reforming trade rules to be equitable for developing countries and providing adjustment assistance to regions and workers dislocated by economic changes. A cooperative system could include global funds or safety nets – say, a global development fund financed by a small tax on international financial transactions or carbon emissions – to reduce extreme inequalities that can lead to resentment and strife. By ensuring all countries have a stake in the system and access to development, the motivations for war (often tied to grievances or resource grabs) diminish. The economic models of collective goods show that when nations jointly invest in public goods (like stable climate, peace, financial stability), each benefits more than if they tried to go it alone. For instance, cooperating on climate change mitigation is far cheaper than each country fortifying individually against climate disasters or, worse, fighting over dwindling resources. A sustainable cooperative economy would treat issues like climate, pandemics, and peace as global public goods problems to be solved collectively.

-

Redirecting Military Expenditure: A crucial aspect of moving from a war-based system to a cooperative one is conversion of the military-industrial complex into a peace-oriented engine of growth. Today, the world spends over $2 trillion annually on the militaryjcfj.ie. In a cooperative paradigm, much of this spending could be rechanneled into productive investment. This does not mean instant disarmament or leaving security threats unaddressed, but rather a gradual “swords into ploughshares” transition. For example, heavy investment in green infrastructure, healthcare, and education across the world could be the new driver of jobs and innovation, replacing the arms race logic. Studies have shown that the same resources create more employment in these civilian sectors than in weapons manufacturing brown.edu brown.edu. Governments can support defense contractors in shifting toward producing civilian products (as was partially done in the 1990s post-Cold War aerospace industry) – a process known as economic conversionunfoldzero.org unfoldzero.org. International agreements can cap or reduce military spending (freeing resources for development) while maintaining a basic deterrent and collective security structure. The theoretical model here is that of a peace dividend: reducing military outlays by cooperation increases overall welfare. In practice, after the Cold War, many nations did reap a peace dividend in the 1990s by shrinking defense budgets and enjoying faster growth and deficit reduction. Unfortunately, global military expenditure has since climbed again, but this trend could be reversed with sufficient political will and trust-building. The key challenge is overcoming the lobbying and inertia of the existing military-industrial establishment – a point often raised since President Eisenhower’s warning about the “military-industrial complex.” Strong civil society movements and international norms would be needed to press for disarmament and conversion, highlighting the absurdity of spending more on instruments of destruction than on saving our planet or uplifting the poor.

-

Meeting Everyone’s Basic Needs Sustainably: Ultimately, a cooperative global economic system would measure success not by conquest or balance of power, but by how well it meets the basic needs of all people. This aligns with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which set targets like zero hunger, quality education, good health, and sustainable energy for all. These are inherently cooperative goals – no country can achieve them alone or by competing aggressively with others. In a fully cooperative world, instead of nations competing over scarce resources, they would collaborate to increase efficiency, share technology, and manage the Earth’s resources wisely. For example, rather than fighting future “water wars,” countries could implement basin-wide water-sharing treaties (many such treaties exist and have prevented conflict, like the Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan which survived even periods of war). Instead of geopolitical rivalry for oil or minerals, nations could jointly invest in recycling, substitution, and renewable energy to reduce pressure on those resources, ensuring sustainability. The incentive structures would shift from zero-sum (if I don’t grab it, someone else will) to positive-sum (if we work together, we can create more than enough for all). Theoretical models like the “global commons” framework support this: cooperative management of shared resources yields better outcomes than competitive exploitation, as demonstrated by Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom’s research on common-pool resources. At the global scale, this means strengthening regimes for protecting the climate, oceans, and biodiversity together, treating them as common heritage rather than fields for conflict.

Historical Lessons: War vs. Cooperation

History offers stark lessons on the costs of war and the benefits of cooperation. The World Wars of the 20th century showed how destructive modern warfare can be: World War I and II caused tens of millions of deaths, razed entire countries, and incurred economic costs far beyond any gains. After WWII, most of Europe and East Asia lay in ruins; it took decades to rebuild, with massive aid and cooperative efforts like the Marshall Plan helping war-torn nations back on their feet afsa.org afsa.org. The lesson learned was that punitive approaches breed resentment (as after WWI), whereas cooperative rebuilding fosters stability (as after WWII). Indeed, the Western allies’ decision to rehabilitate Germany and Japan and integrate them into a new world order was vindicated by those nations becoming prosperous democracies rather than enemies. This paved the way for an unprecedented era of great-power peace – there has not been a direct war between major powers since 1945, in part due to institutions like the United Nations, NATO, and the European Union which were explicitly designed to promote collective security and economic cooperation. While proxy wars and conflicts persisted, the second half of the 20th century saw global per-capita GDP grow several-fold, life expectancy rise, and numerous countries emerge from colonialism into nationhood, suggesting that relative peace (despite a tense Cold War) created space for development.

During the Cold War, however, the world also witnessed a colossal waste of resources in the U.S.-Soviet arms race. Trillions were spent stockpiling nuclear weapons and conventional forces that, thankfully, were never used. This arms buildup did little to improve people’s lives; in fact, both superpowers neglected domestic needs at times to fund the military competition (the Soviet Union’s economy ultimately collapsed under the strain). When the Cold War ended, there was hope for a “peace dividend” – and indeed the 1990s saw reductions in military spending and a surge in international cooperation (e.g. peacekeeping missions, humanitarian interventions, global treaties). However, the 21st century has seen new conflicts and a resurgence of nationalist rivalries, reminding us that the default of history is conflict unless conscious efforts are made to cooperate. The ongoing wars in regions like the Middle East, and now Europe (Ukraine), show how quickly the costs pile up when diplomacy fails. For instance, Syria’s civil war since 2011 has not only killed hundreds of thousands and displaced millions; it has also cost an estimated $35 billion in lost output by 2016 (equivalent to Syria’s entire pre-war GDP)worldbank.org, essentially setting the country’s development back by decades. On the other hand, there are success stories of cooperation preventing or ending conflict: international diplomatic efforts helped end apartheid in South Africa peacefully, regional cooperation in Latin America has kept the region largely free of inter-state war in recent decades, and the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland showed how dialogue and power-sharing can resolve a violent conflict that had raged for generations.

In sum, history teaches that war’s apparent “wins” are pyrrhic and temporary, while the gains from peace accumulate over time. No nation that has experienced war’s devastation ever wishes to repeat it – consider Japan’s post-WWII constitution renouncing war, or Europe’s deep commitment to union after centuries of bloodshed. The economic “golden ages” that people look back on (the post-war boom, the 1990s tech boom, etc.) all occurred in conditions of relative peace and stability. Conversely, periods of widespread war (1914–1918, 1939–1945) were times of immense human and economic loss, even if some industries boomed in the short run. As one analysis noted, developed economies may sometimes see a short-term uptick by participating in wars (especially if fought elsewhere), but globally we all end up poorer – by an average of 12% of GDP lost since 1970 due to conflicts warpreventioninitiative.org warpreventioninitiative.org– than we would be in a peaceful world. The “logic” of the military-industrial complex can trap us into perpetuating conflict, but society at large bears the cost warpreventioninitiative.org. Thus, shifting to a cooperative global system is not just idealism – it is pragmatic when one tallies the full costs.

Conclusion

Weighing the evidence, the cost of war – economically, socially, structurally – is astronomically high, far exceeding the cost of pursuing peace and cooperation. War may bring brief economic blips for some sectors or nations, but it fundamentally acts as a drag on long-term growth, a destroyer of lives and wealth, and a generator of instability. The supposed economic benefits of war, such as military-industrial output or technological spin-offs, do not outweigh the destruction and deferred costs; indeed, similar or greater benefits could be obtained through peaceful investments without the horrific loss of life and property that war entailsvisionofhumanity.orgvisionofhumanity.org. In contrast, the cost of cooperation – funding diplomacy, sharing resources, building international institutions – is comparatively trivial and yields compound returns in the form of a stable, thriving global society. As the data shows, even a small reallocation of world military spending could eliminate basic scourges like hunger and illiteracy unfoldzero.org, demonstrating the untapped potential of a cooperative approach to global development.

A sustainable cooperative global economic system would function on principles of mutual benefit, fairness, and foresight: nations working together to solve common problems and lift each other up, rather than attempting to dominate or destroy. This doesn’t happen automatically; it requires enlightened leadership, trust-building, and often a reframing of “national interest” to align with global interest. Yet, institutions from the UN to regional alliances provide a platform, and treaties and norms – if respected – can gradually replace violence with dialogue. Theoretical models in game theory and international relations reinforce that when communication and trust overcome fear and aggression, all parties can achieve better outcomes than in zero-sum confrontation. In practical terms, investing in peace pays off richly: prevention is cheaper than cure, and creation is better than destruction. The economic, social, and structural benefits of peace – greater prosperity, healthier and better-educated populations, resilient infrastructure, and the chance to tackle global challenges like climate change cooperatively – far outlast the fleeting booms of war. As one assessment succinctly put it, “Putting a price tag on peace and violence helps us see the disproportionately high amounts spent on containing violent acts compared to what is spent on building peaceful societies.”weforum.org

The verdict is clear: humanity’s wealth and wellbeing are best served by the path of cooperation over conflict. In an interconnected world facing shared existential threats, the only truly sustainable victory is one where we all win – a peace won not on the battlefield, but at the conference table and through collective endeavor.

Sources: The analysis above is supported by data and research from the Institute for Economics & Peace, World Bank, United Nations, academic studies on war economics, historical accounts of post-war recovery, and various economic reports and models that quantify the impacts of war and peace

Recent Comments